On the rigidity of recipe writing.

Is recipe writing a lost art? Or do we all conform to a set style for a reason? Also: why headnotes are my favourite part of a recipe, and why I find my own debut cookbook frustrating to cook from.

Today’s essay is not about an ingredient specifically, but it is about what most of us turn to when we have a bunch of ingredients we want to make something delicious out of: recipes. As a professional recipe developer, both as myself and as a ghost writer I spend more time than most pondering how to present a recipe on a page. But with no set degree or recognised professional school teaching us how to write a recipe for someone to replicate at home, how one writes a recipe can be left up to interpretation.

I’m super excited about July’s theme for ingredient, which, assuming my ice cream maker cooperates (and I can make space in the freezer for the bowl after my meat delivery arrives at lunchtime!), should be with you promptly on the first Thursday of next month. As ever, be sure not to miss out by becoming a subscriber here.

It started with an argument about capers.

Well, I would not call it an argument as such, but it was certainly a disagreement, and whilst the capers were just a small detail that made up part of a bigger picture, for me they represent why I enjoyed publishing my second cookbook so much more than my first.

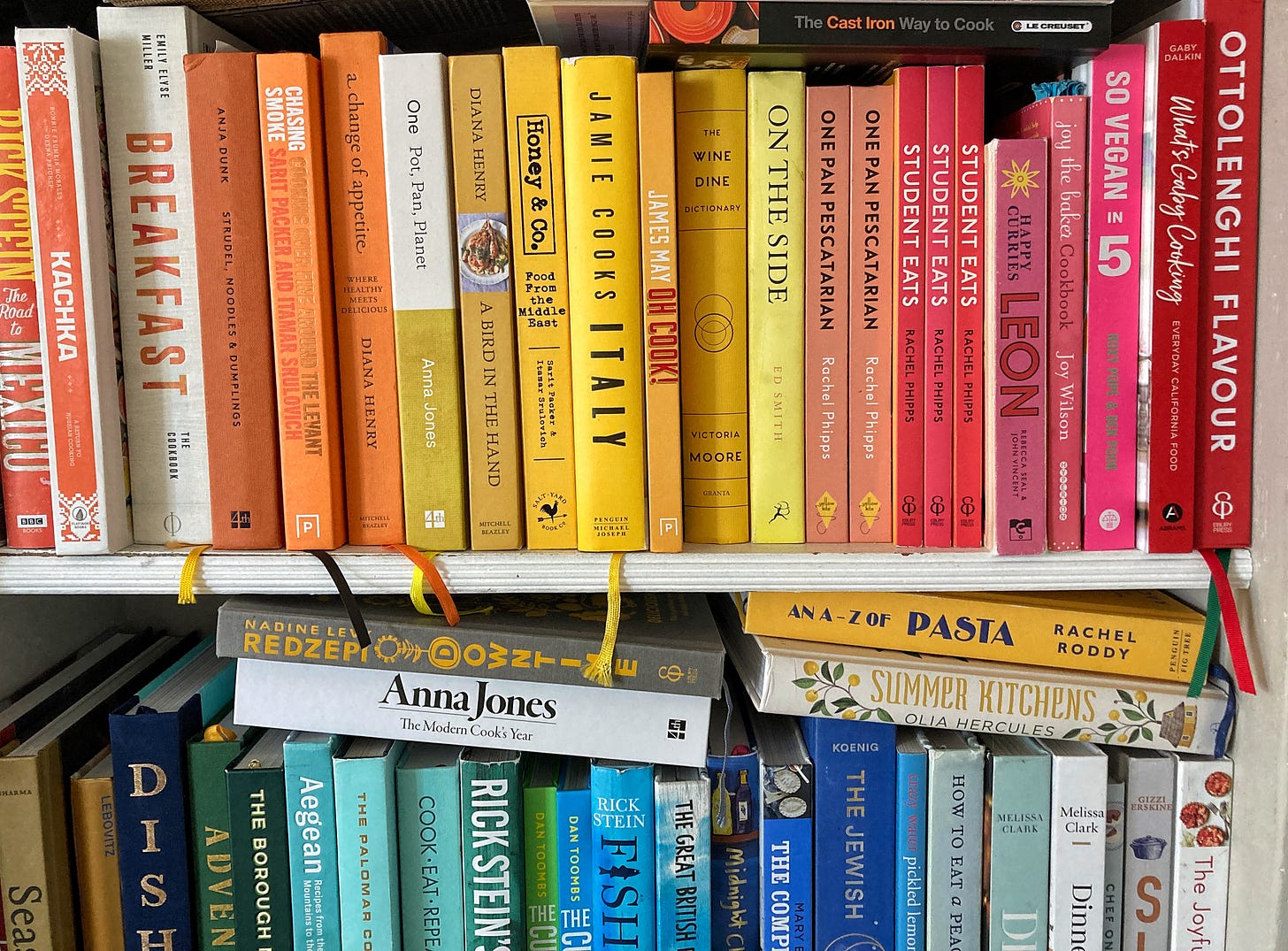

I probably shouldn't say this, but I don’t enjoy cooking from my first book, Student Eats. As a first time author at one of the worlds biggest publishers, you don’t get much of a say in anything. I still don’t like ‘Student Eats’ as much as ‘Student Bites’ for the title, I saw the cover for the first time when it was uploaded to Amazon, and I find the ingredient lists almost impossible to cook from.

I think it was my editors idea: as this is a book for students, why not separate the lists into ‘fresh’ and ‘store cupboard’? It will help people shop?

I never felt comfortable with this, my argument at the time being that yes, I’d suggested at the front of the book some useful ingredients to keep in the cupboard, but who exactly is going to follow this to the letter, even a student who is stocking their first kitchen? And this system assumes that everyone has all of these in stock and has never run out when planning to make a recipe. That would be the only way the two lists would not end up utterly confusing.

Now, my issue with the ingredients being in two lists is obvious as a recipe developer with a lot more experience: ingredients are listed in the order you need them so you can ensure nothing is left out. This is sensible, logical, and so widely adopted deviating from this is why I find my own cookbook frustrating to cook from. On a deeper level, it hurts me that some of my best recipes, along with some family classics are stuck in a format that will equally frustrate anyone trying to recreate them at home.

So back to the capers. Over on her Substack at the start of the month, food writer (and more importantly, food writing teacher) Dianne Jacob published a piece entitled ‘On “In a bowl, combine…”’, lamenting the ‘lost’ art of recipe writing:

I encourage you to click through and read the piece, but the crux of it is that by sticking to rigid, clinical instructions we’re losing some of how we as recipe writers are able to connect with the people using our recipes in their homes. She expressed this view on Twitter, and was met with a lot of disagreement, particularly from the British food writing contingent, where whilst I can’t figure out why this is, I feel we are expected to conform to the status quo a lot more than American food writers. The main overarching argument of the critics was that concision matters more in recipe writing than personality.

I love sitting down to read a cookbook written by Nigella Lawson, or Nigel Slater, or Diana Henry, because how they write their recipes - not just the headnotes, but the recipes themselves - is so lyrical. But I also read them with a slight bitterness because whilst I’ve been able to push the envelope on expected and accepted writing styles with each book I publish (for example I adore long form food essays in cookbooks, and I never asked permission to put them in One Pan, I just submitted the manuscript like that fingers crossed, and got away with it and a warning that if they took up too space they would have to go rather than reduce the recipe count to keep within the number of pages they’d budgeted for) as a freelancer, I’d never get away with deviating from the accepted style of how one writes a recipe - even when it has my own name on it.

Dianne introduces her piece quoting cookbook editor Judith Jones (who edited Julia Child and Claudia Roden, among others) who laments the very issue both of our pieces are based around and it leaves me wishing I was allowed to step outside the set guidelines that are accepted on recipe writing, but I’m not one of the above big names so I simply won’t be allowed to get away with it. Just like how as a debut author at one of the worlds biggest publishers, at an imprint that publishes Yotam Ottolenghi and Mary Berry, I did not have enough success behind me to overrule a silly decision about ingredient lists that is going to fuel my love / hate relationship with my first book for the rest of my life.

I know why editors and publishers are rigid about recipe writing styles: they don’t want to be left with a social media (as well as traditional media) fall out when recipes don’t work. And it plays into the status quo that the more successful you are, the more you can push the boundaries: if you’ve ever sat in a publisher meeting trying to sell a cookbook proposal in the modern era as someone just starting out, your social media following is just as important as, if not more so, than the quality of your voice or the accuracy and creativity of your recipes. I found myself discussing this at a literary festival with Diana Henry once, when she’d just published How To Eat A Peach (a beautiful, seasonal book of entertaining menus and recipes finished with a gloriously fuzzy, peach-like cover: a concept and a printing cost that publishers would only ever sink into a guaranteed seller) and she lamented all the profile building on social media my generation of food writers are locked into doing which just was not a concern for her. I think this way publishers have settled on for guaranteeing book sales before commissioning a project is stifling creativity.

If you trawl back through my blog into the archives you’ll find how I write recipes has changed over the years, and as it is the first professional style sheet I had to adhere to I know there are echoes of the BBC Food style sheet in my recipe writing here on Substack, on my blog, and pretty much everywhere I write recipes as me. I now find it difficult and unnatural to do it another way when I’m ghost writing. Yes there are some quirks I know make it into my copy which editors remove later; for example I religiously list ‘light oil’ as the cooking oil for most recipes to let both the reader and the publication pick, unless it really matters to a recipe (and most cases it doesn’t). I find light olive oil, vegetable oil, sunflower oil etc. pretty much interchangeable, but set as part of the bigger picture it is a pretty small act of rebellion.

Writing this essay I’ve also looked back over some of my most recent recipes, to see exactly how I introduce ingredients and equipment. In my just published recipe for Curried Potato Pasties I direct the home cook to:

In a food processor blitz together the flour, turmeric and salt with the butter and lard until you’ve formed crumbs. Little by little, blitz in splashes of ice cold water until the pastry comes together into a dough.

I’ve started with the food processor because you need that on the counter before you can add anything to it, just as best practice is to write the ingredient lists in the order you’ll need them. On reflection, I’m not sorry for this. But, I do note that I’ve not asked for the lard or the butter to be cubed, which will provide best results in this recipe, assuming in order to measure it you’ll be cutting pieces onto a scale (remember I’m British, I don’t use cups unless asked to do so, and I will never stop thinking that a tablespoon is the most illogical measurement to apply to butter which is not always melted or softened to room temperature) - but, in a processor, you’ll be fine. I’ve not been rigid, as rigidity here is not 100% necessary for success. I also think recipes that are so prescriptive they remove agency from the home cook are belittling.

In my Chilli Garlic Courgette Stir Fry recipe I dispense with kitchen equipment completely instructing:

To make the stir fry sauce, combine the fish sauce, soy sauce, oyster sauce, black vinegar, honey, sambal oelek and 2 tbsp of water, and set aside.

I’ve made the (I think fair) assumption that someone will know to reach for a bowl and measuring spoons to make the sauce, because that is the most logical way to do so, but if they wish to mix this in a glass or a mug, or if they have one of those little measuring cups that have all the spoon measures marked on them, because it won’t matter to the recipe if they deviate form the norm, they can be my guest.

In Mummy’s Israeli Salad I’ve been very rigid in my instructions:

Finely dice the cucumber – don’t bother peeling it – and toss it with the 1 tsp sea salt. Set aside in a colander to drain.

This is a very precise recipe for authentic tasting results, so everything here, from the fine dice, to the skin, to the colander are essential. I’m not sure if adjusting the language will hinder, rather than help the clarity needed here.

One thing I think it is a shame Dianne did not mention in her article is the art of the headnote, one of my favourite parts of any cookbook, and something I’m sad my BBC work lacks. If we are accepting the argument that a recipe that follows the ingredient list structure of introducing equipment in the order you need it stands true, I think the headnote introducing the recipe is where the art of good food writing rests. They are what I enjoy writing the most, and it is what makes me sit down and read a good food writers cookbooks almost cover to cover, skipping over the directions until I come back to cook something later, unless something in the headnote has particularly peaked my interest.

In an email I asked Dianne for her thoughts on headnotes and she told me:

(That headnotes) are a chance to engage directly with the reader through narrative: to tell a story, give a history lesson, expand on a technique, explain an ingredient, or give some tips and variations. Without one readers go directly to the ingredients list, which is much less fun to read, ex. "4 eggs.”

I would contend that she is exactly right about headnotes, but I’d take things a step further: headnotes are where the story of the recipe should live, not down below, clouding the directions.

But back to the capers.

I specify nonpareille capers in all my recipes. They’re smaller, I think a little more flavourful than regular capers, but without the punch of caper berries. I also like how easily you can pack them into a measuring spoon for almost accurate measures without having to plop something so tiny down on the scale. But when I got my first pass sheets (big A2 print outs of my book for me to review and scribble over once the brilliant designer had set my recipes and the corresponding photos into layouts) the project editor had changed this to simply ‘capers’.

I changed it back in my notes, and added into my accompanying email that they’re a different product, and for my recipes they needed to be nonpareilles. I soon discovered my editors concern: they wanted my recipes to be accessible for the average cook (quite understandable in a book focusing on weeknight, one pan recipes) and not be pricier or harder to find than their alternatives. There was some back and forth. I used the wonder that is the internet and online grocery listings, as well as trips to every supermarket within walking distance of my old flat in East Dulwich to prove that my beloved nonpareilles were not only just as available, but sometimes cheaper than their plumper fellows. I won the argument, and One Pan Pescatarian proudly boasts nonpareille capers in its recipes.

The experience of writing my first book taught me to pick my battles so I could stand my ground where it really matters; incidentally, publishers do do things for a reason and are right much more than they are wrong. I still love the pink cover for One Pan two years on and going with the blue I lobbied for in meetings would have been a mistake (if you’re interested, I wrote about how we designed the cover here!)

I think the art of writing the perfect recipe is all about balance; balancing what makes the recipe matter; it’s provenience; it’s story; the why (as in why it needs to make its way into your kitchen); and accuracy and accessibility: it needs to be as clear as possible so anyone trying to follow it has the greatest chance of success.

It drives me around the bend both as a food writer and a food blogger who makes a substantial chunk of my income from my blog when people rant ‘why do you have to give your life story before a recipe why can’t you just give us the recipe’ not just because without it you’d just be getting the recipe for free and I’d not be able to pay my mortgage (longer posts allow for more ad placements, and all that text is for SEO - search engine optimisation, playing Google’s game to get to the top of their search results - so again more people can get eyeballs on those ads) but because that information is just as important as an accurate recipe in, well, making a recipe important, and setting it apart from just another way to make a lasagna. It is why I love Substack so much, because the more of you who become paid subscribers, the less of my recipe writing time will be taken up by trying to build my ad revenue to pay for ingredients.

What I think I’m trying to say is thy rigidity on recipe writing can be both a good thing, and a bad thing, depending on how it is applied.

My Ma-ma’s original Lockshen Pudding (yes I know that is not how you spell it, but it is how it was written down for me so I’m keeping it - it’s part of the recipes story) directs you to make a ‘mush mush’, (always pronounced by her as ‘moosh moosh’). It is what makes it ‘her’ version of the classic Jewish comfort food, but unless you’ve stood at the counter watching her ‘mush’ together raw eggs, margarine, dried fruit and spices with a white plastic Delia Smith spatula before folding in the cooked egg vermicelli, the direction is utterly useless.

Just like the way the ingredients are listed in Student Eats, this is yet another example of why things are done a certain way for a reason.

What do you think? Because I think there are too many pros and cons in how recipes are written to count, and after excusing almost 3,000 words on the subject I think I need to hear from people who follow recipes every day, rather than write them.

This is a great read, Rachel, and has so many excellent points. As someone who has spent way more time reading and trying recipes than writing them, I think the best way to write instructions for the home cook really depends on what you’re making. If it’s something more complex, I certainly appreciate having the equipment listed first, as in your food processor example. In an ideal world, we would read carefully through the recipe and instructions first, but listing the part about the equipment first helps it to not be missed. Also sometimes it really does make a difference if you use a large bowl or a small one! I’m thinking of a recipe I make fairly frequently that specifies using a large bowl in the first step because later in that same bowl you have to add chicken (and if you choose a small one it’s not all going to fit). At the same time, I agree that if you’re making a sauce or a dressing, it’s much less important to explain to the reader what recipient they need to choose.

Good for you for winning the argument on your nonpareille capers (side note that these are always the capers I reach for and I agree that they’re more flavorful)! It’s interesting that British publishers may be more strict than their American counterparts, and I guess in a way it makes sense, at least from a language perspective. Your comment actually made me think of the Oxford English Dictionary vs. Merriam-Webster. It’s my understanding (and please someone correct me if I’m wrong!) that it’s much easier for a word to make it into Merriam-Webster when compared to the OED, especially when it comes to more of-the-moment words like internet slang. Maybe in the same way there’s more of a sense of following tradition for British publishers? There are pros and cons to both styles, I suppose- it’s nice to be allowed some leeway, but too much could lead to disastrous results, particularly for something like a cookbook.

Writing about recipes is hard. Thanks for the effort!