On making the perfect Yorkshire pudding.

If you grew up in the 90's forget everything you were taught about how to make Yorkshire puddings.

If you’re planning on roasting a joint of beef this weekend, if you learned to cook as a child and you’re a British Millennial like me you probably learned to make Yorkshire Puddings from the same recipe I did. Which means you’ve probably been doing it wrong. So, today as a sort of recipe add on to my Flour feature, I’m discussing how I manage to get perfect, puffy, golden Yorkshire puddings with crisp shells and squidy middles every time for a foolproof, scalable recipe you’ll want to bookmark forever.

I’m just having a bit of a final play with this months ingredient recipes and essays before I get in out to you all as well as this months super exciting Kitchen Cupboards feature from a writer I adore cooking and shopping for ingredients somewhere far from home, so be sure to subscribe now not to miss out on future essays, recipes and features!

It turned out that the key to making the perfect Yorkshire pudding was to forget everything I’d been taught about making Yorkshire puddings. In doing this I have become our families undisputed Yorkshire pudding maker, alway producing the tallest, lightest, crispest puddings with the softest, densest middles (from henceforth called the balance between puff and squidge).

There are routines that J and I like to structure our lives, and one of these is our Sunday roast. Be it a plump Pipers Farm Chicken1, a piece of pork or beef from Gibson’s or a leg of lamb at my parents house (prior to this week we could not quite afford to roast lamb ourselves at home, and we were unimpressed the one time we tried roasted mutton, but I got the shock of my life yesterday to find that the price of beef had actually outstripped lamb so I snagged a small half leg) we always try and have a traditional British roast with all the (suitable) trimmings every Sunday night.

By suitable trimmings, I mean paired to whatever meat we’re eating. I know pubs tend to just pile all the trimmings onto whatever meat you order, and whilst I’m not complaining about this, there is a proper way of doing things that is flavour as well as tradition forward. Roast lamb comes with mint sauce, and sometimes redcurrant jelly2, pork with crackling, apple sauce, maybe a bit of stuffing and possibly mustard, chicken with pigs in blankets if we’ve got them, and beef (once you’ve chosen between creamed horseradish and mustard), and only beef with a Yorkshire pudding (or three. You don’t want to know how many my family have seen me eating in one sitting before…)

Partially because I wanted to share this important British weekend classic with you all as I’ve noticed a whopping 50% of you hail from the USA with only 13% of fellow Brits subscribing, and also because I wanted to stick my recipe somewhere I could easily access better than scrolling through Instagram to where I last posted this during the original Covid lockdown (I have a terrible memory for even my own recipes and the only thing I have memorised is the sandwich loaf I make multiple times a week) this is how I get them perfect every single time.

Now, a few notes before we get started:

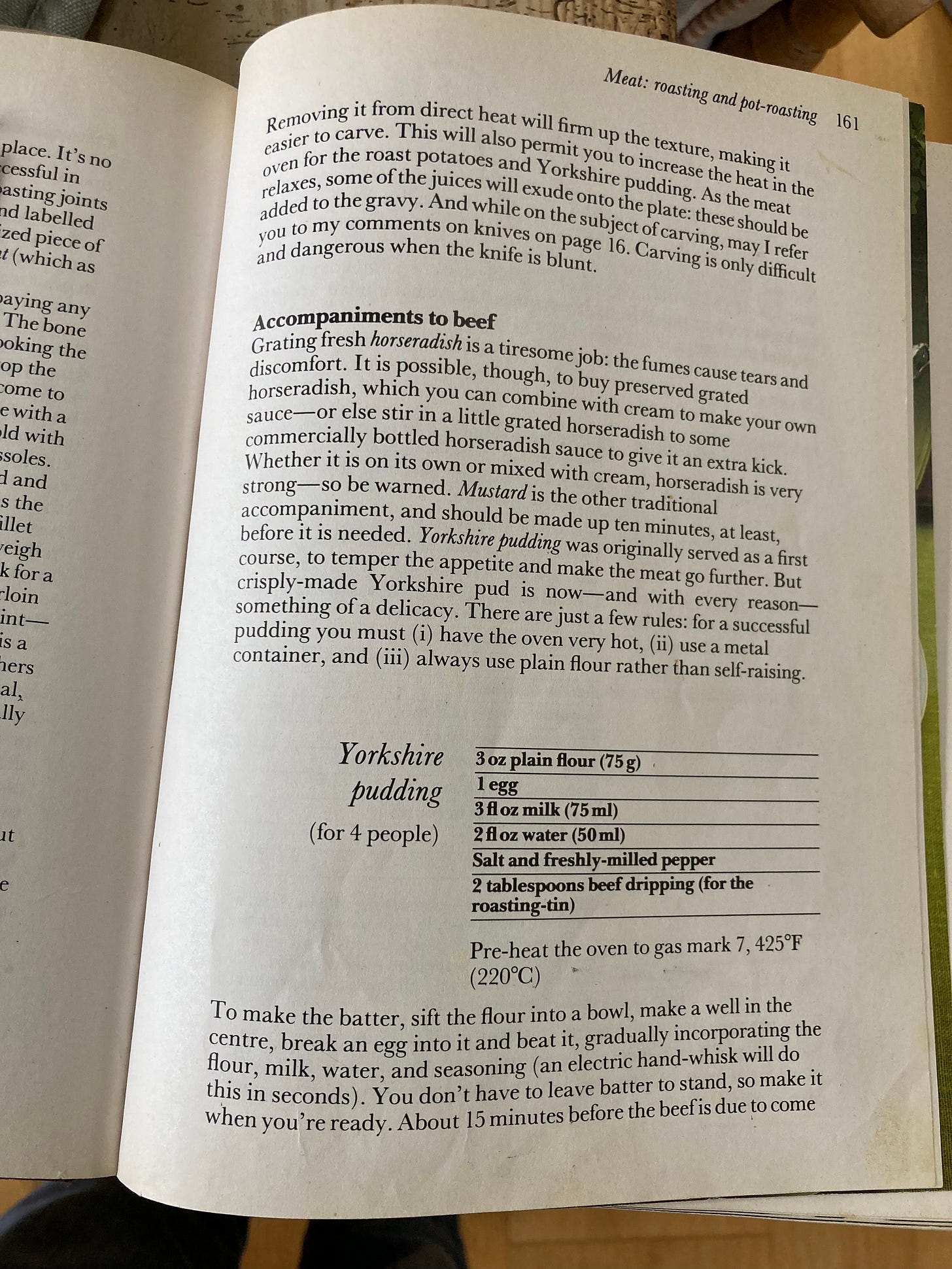

The Problem With Delia Smith

Above is the Delia recipe I grew up with from her famous 1978 book Delia Smith’s Complete Cookery Course. I remember vividly standing at the central aisle in my parents kitchen overseen by my grandmother as I measured, sifted, made a well, and gradually added the liquid, whisked separately. It was a faff, and I blame this faff for the horror of Aunt Bessie’s Frozen Yorkshire Puddings that was to be had at my other grandmother’s house, and sadly in households across the land.

Now, anyone who has sat down to discuss famous British cookery writers with me before (hello Anne, hello Annette!) will be aware of my deep dislike of Delia Smith as an entity in the British food space, her food writing, and her recipes. Whilst she is how many people learned how to cook, I find her writing unnecessary and infantilising, and I believe the only book she’s ever produced of value is is her (actually, annoyingly rather good) Christmas book from which our family stuffing recipe hails.

But there is also no escaping that she was in Britain what Mary Berry was to baking, back before journalist Nigella realised she wanted to write a cookbook, or a young Jamie joined the team at The River Cafe where he was discovered by the media.

The above is how we were told we should make Yorkshire puddings, and all the other recipes from books at the time I remember, and even many more modern ones are simply just variations on a theme.

Until the day I got lazy, and, cutting down the ingredients to serve just the two of us where making a well would be a little difficult, I just dumped everything in a jug at once and whisked. My batter was not smooth like I was always taught it should be, but those Yorkshire puddings. I’ve never made them another way again, and it has made my life so much easier. It has turned making them into a task just as easy as every other trimming I’m making for our roast.

There is not much with the ingredients list itself I disagree with (though I personally don’t use water, but I know some people say it adds extra rise and crispiness, but my Yorkshires have never needed this) and 220C (fan) is close to what I use when they’re by themselves in the oven when the potatoes and beef are in my parents AGA; otherwise I’ve found anything from 180C works depending on how you’re cooking the beef, just keep an eye on them and adjust the cooking time accordingly. I’ve never understood across the board listed quite high Yorkshire cooking times as I know it is not normal to have two ovens; yes the meat might and probably should be out and resting by now (unless it is a tiny joint), but what about the potatoes? They’ll burn at that high a temperature most likely, and when done properly they don’t sit out or keep warm well. It is why they’re usually much better at home than in the pub. Ditto with the Yorkshires.

So perhaps I don’t agree with the cooking time after all.

But I digress back to the faff of this recipe. I think the faff is what used to put so many people off. The faff is why I’ve eaten so many strangely uniform frozenYorkshire puddings in my life.

Ingredients

Obviously, flour is key. Regular plain flour here I find is best, though the world did not end when I’d run out and I used the strong Canadian white I buy for bread making.

I prefer large eggs for all my baking, but again, sometimes I’ve had medium to hand for clients who prefer those and I’ve still had tall, decent Yorkshires. A small egg would throw the ratio off a bit too much, though.

Lots of recipes I’ve seen call for whole milk. I honestly don’t see a difference using the whole I’ve bought for specific recipes versus the semi skimmed we usually buy. I’ve not tried skimmed milk in this recipe because the one time it arrived in a grocery order by mistake I discovered it is basically water so I’ll never write it into one of my recipes. I don’t see the point.

Cooking Fat

Growing up, my mother taught me to make Yorkshire Puddings using either melted vegetable shortening, or light olive oil. She used to use shortening for the roast potatoes too and now we both usually use light olive oil, so I think she must have switched about the same time. It was the 90’s and the oil was becoming cheaper, more available, and we were all told how much better for us it was. All I know is it tasted better.

Something else I’ve tried (hat tip to my friend Chris who just so happens to be the two time world champion at making Yorkshire puddings) is using beef dripping. Yes this had the best flavour but for every beef weekend - just like I only do my potatoes in goose or duck fat if it is a special occasion or I’ve got some to use up - I’ll stick to the olive oil to preserve my arteries. The duck and goose options also yield delicious results, too.

The Cooking Vessel

The top picture shows Yorkshire puddings done in a non-stick muffin tin (if you do it often keep one just for Yorkshires as it will deteriorate and then you won’t want to use it to make muffins) which is what I opt for it if I’m cooking for 3 or more people using a 2 egg or more batter. Nice and traditional.

However, at home cooking for just the two of us I just make one rectangle Yorkshire in this 19cm (1.1L) Le Creuset mini baking dish I do use for other things but ordered specifically for the purpose after my same sized oval one I’ve been doing Yorkshires in for years broke. Working to that scale and at that depth, cutting the large pudding in half with scissors just before serving I find you still get the perfect puff-to-squidge ratio.

I don’t however recommend the baking dish method for more than a one egg batter. When people do this I’m always fighting to get a delicious middle piece that is all squidge. But that is personal preference; make it in too big a dish and people who prefer either puff or balance might be disappointed.

Popping back to Le Creuset for a moment, I did flirt with the concept of getting one of their Yorkshire pudding trays for a while (dangerous things like this sometimes happen when you only live 15 minutes from a Le Creuset outlet store) but I am suspicious that again, they won’t yield the right balance of puff and squidge.

Perfect, Scalable British Yorkshire Puddings

Serves: 2, or 4, or 6, or 8 (you get the gist!)

light olive oil

35g plain flour

1 large egg

50ml milk

freshly ground salt & black pepper

Pre-heat the oven, if it is not already hot and loaded up with beef and potatoes to 210C (fan). Pour just enough oil to cover the bottom of your dish / two holes per egg of a muffin tin and stash in the warming oven.

Dump the flour, egg and milk into a jug or bowl and season with more salt and pepper than you think it needs. Whisk until you have a uniform batter. You can do this up to an hour ahead; resting does improve the texture, but if you’re making them last minute they won’t be impacted enough that you’ll regret having Yorkshires!

Once the oil is shimmering pour the batter into the middle of the dish / to 1/3-1/2 fill the holes. Cook for 15-20 minutes until puffy and golden, possibly a little longer if your oven is a little cooler to accommodate the beef and potatoes. You’ll know when they’re done by sight and they’ll never take more than 30 minutes.

Serve as soon as you can, juggling the carving and the gravy.

One of my favourite online butchers - use this link to get £10 off your first order (I’ll get 1,000 Pipers Points if you sign up which I can put towards things like vouchers and free delivery!)

I got caught up in the thought of a Le Creuset outlet store...and learned there’s one a half hour away! Field trip!

Couldn't agree with you more fellow British millennial. Just subscribed 😌